The TL;DR key points

Making an impact: Why you should care about itImagine that you’re 80 years old, looking back on your life and all the things you have accomplished. What would you like to see? Perhaps you’d like to see that you had a happy life, a family and success in some line of work. But I suspect you’d also like to see that you had made a positive impact in some way: that somehow others benefited from your existence. After all, when we step back to consider the question, what beauty is there in a life lived only in pursuit of one’s selfish ends? Presumably, then, this has implications for now: presumably we’d like to make a positive impact while we still can. And given that the world faces a diversity of challenges, such an impact is desperately needed. But where do we start? We all know about two high-profile challenges: the coronavirus and racial injustice. So maybe we could start there. Or how about healthcare? Shane Boyle, for example, died after he couldn’t raise just another $50 to fund his diabetes medication. He is not alone. One study estimated that as many as 44,789 Americans died because they could not afford medication in 2005. Meanwhile, drug companies have been rising prices to maximize profit, the most notable example being an increase of one important medication from $13.50 to $750 a pill. So healthcare is one challenge, but what about poverty in general? One study claimed that in 2000, approximately 133,000 deaths were attributable to poverty afflicting individuals in the United States. Or what about mental health? Over 45 million Americans are experiencing mental illness, about 20% of the population. Over 10.3 million have suicidal thoughts, while over 48,000 people died by suicide in 2018. Or what about the myriad other extremely important challenges facing the world? Climate change? The pervasive sexual harassment and mistreatment of women? International conflicts costing millions of people their lives? Environmental pollution? The extinction of species at accelerating rates? Corruption? Homophobia? The myriad specific diseases out there? Believe it or not: the point is not to depress or overwhelm you. Instead, the point is that if we consider all these problems, one thing is clear: you cannot directly address them all, but they are all extremely important—and their importance cannot be overstated. Being a changemaker and making changemakersBut how does one go about making change in world of so many challenges? One option is to be a changemaker: to focus on one or a handful of issues, hopefully making some progress on them. Of course, this is both necessary and extremely praiseworthy. But another option is make changemakers: to empower growing numbers of people with the motivation and competence to make a positive impact. The difference is between solving problems and creating problem solvers. It’s like giving a man a fish and teaching a man to fish—focusing on long-term solutions with potentially greater payoffs and impact. We could visualize this more concretely with a illustrative model. Suppose there’s 5 people considering how they can make an impact over a 15-year period. They have two options: they can either be changemakers or they can make changemakers. Let us make some assumptions about the impact which they can have with each option. Of course, these assumptions are over-simplifications, but they potentially illustrate an important truth which I'll touch on later. Here are the assumptions:

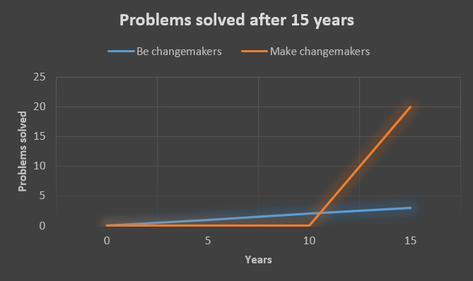

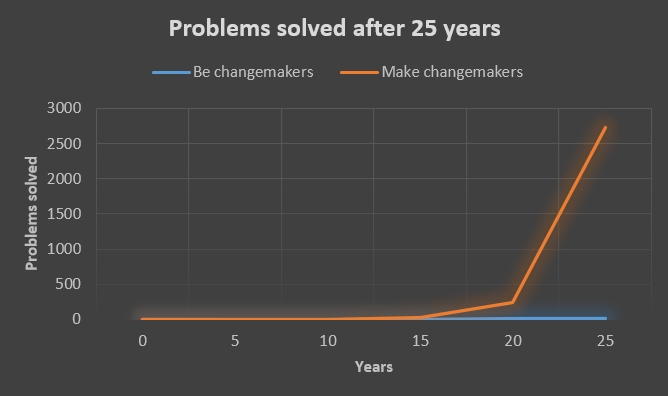

If we make these assumptions, then we can plot how much impact those 5 people would have when they are changemakers versus when they make changemakers. Here's a 15 year projection: However, it makes an attractive impact after 15 years. 20 problems are solved when making changemakers whereas only 3 problems are solved when being changemakers. But really, the most pronounced difference is what happens after 25 years: Of course, the natural reaction to this graph is to question how realistic the assumptions are, especially since they're undoubtedly over-simplifications. (Actually, you can play with the assumptions in this spreadsheet yourself if you like.) The purpose of this graph, however, is not to have precisely accurate assumptions—something which I suspect is neither possible nor desirable at this stage. Instead, it's to make two points. First, there may very well be some kind of relationship like this, where education generates vastly greater payoffs over the long-term. As my collaborators Will Roderick and Jake McKinnon point out, even making just one other effective changemaker increases your impact in a big way. Second, we do not know what the realistic assumptions are. Perhaps it is harder to educate 100 changemakers in 5 years, since it might take time to develop materials. Or perhaps it is easier to educate 100 changemakers, since we could build on existing programs and work with them. Likewise, for each of the other assumptions, there are arguments in both directions about what the more realistic replacement is. The point is that there is much that we do not know. But the potential payoffs of this line inquiry could be tremendous—incomparable even. While we don't want to jump to conclusions about what is possible, we also wouldn't want to jump to conclusions about what is impossible. Who could have anticipated the impact of the internet or of mobile phones for example? Could an effective education program likewise change the world in hard to fathom ways? Who knows. But it seems to me to be worth exploring--and with an open mind. The project: Some questions for explorationSo the aim is to explore the potential of education, guided by the idea that it might play an incomparably important role in social transformation. What questions need to be asked in exploring this topic, then? Well, perhaps we could group them under several categories. There's questions about existing programs and possibilities:

Then there's questions about the design of programs:

Then there's also questions about how the project runs:

And we also have more logistical and practical questions about the project's immediate operations:

To some extent, the current collaborators have explored these questions already, some of us in papers we've written and others through our experience in organizations. But the purpose of the project is to further explore these questions to probe the potential of education. What does participation look like?Assuming one is interested in the project, what could participation involve? Here's my initial response: anything ranging from "not much" to "lots"—it depends on the interests and availability of the person. At the "not much" side of the spectrum, even coming to a Zoom chat occasionally to listen to ideas and share opinions can be valuable. Often, everyone has something valuable to contribute, and we wouldn't want to preclude their participation, especially if they find the ideas interesting. At the "lots" side of the spectrum, someone may wish to take this on as a full-time job, applying for grants and pursuing this research as it interests them. Then, there are various mediums between these extremes. For example, someone might like to:

Really, it depends on the individual, but the important point is that anything helps and is welcome—but without further expectations. Who could participate in the project?Of course, the project touches on many questions from various fields: education, management, psychology and philosophy—to name a few. But not everyone has a background in these things. So who could participate? Here's my suggestion: everyone who is willing and able—but in a sense which I will soon describe. The rationale for this is twofold. First, a growing body of research suggests that background expertise, while useful, is not necessary to be proficient in particular domains. The most striking example of this comes from four decades of research into geopolitical forecasting. There, thousands of people make predictions about future events—like the outcomes of elections, wars, pandemic and economic events. One of the most startling findings of the program was that typical indicators of competence actually didn't correlate with success: it made no difference whether one had a PhD, many years of experience or even a full-time profession giving their opinions to the media or important organizations (Tetlock, 2005). In fact, many "experts" on political matters turned out to not be that good. However, others were remarkably good at predicting the future—in fact, they even outperformed intelligence analysts with classified information and indeed any other prediction mechanism that we know of (Tetlock & Gardner, 2015). These people—the "superforecasters", as they're called—often came to questions with no strong background knowledge: they might have to make predictions about the "UNHCR" without even knowing what that is at first. But the point is they even if they don't know a lot, they would learn a lot--and they're impressively good at what they do. Furthermore, the research shows various things can make people good (Chang et al., 2017; Haran et al., 2013; Mellers et al., 2014, 2015; Tetlock & Gardner, 2015). These things include:

So when I say "willing and able", I mean everyone who is seriously willing to develop these qualities. The research suggests all these things make one a better forecaster. But upon reflection, it seems clear that they could make one better in many domains which they apply themselves to. My point is that what's most important is not so much the expertise which people have, but rather whether they have the qualities that could predict future success across many domains. My second reason for thinking that everyone can get involved is that others have successfully worked in areas that were not always their own. This is true in education: FUNDAEC has successfully implemented education programs across Latin America, for instance, despite being championed primarily by a physicist and a mathematician. But this is also true in areas outside of education as well: Jeff Bezos was just a smart Princeton graduate in electrical engineering and computer science, but he did remarkably well in turning a book company into the world's most profitable business. What, then, could a group of Stanford graduates accomplish? If you're interested in the project, don't hesitate to contact John at [email protected]. References

1 Comment

Patricia Wilcox

11/23/2022 01:27:36 pm

Love this.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorJohn Wilcox Archives

January 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed